The Scent of Lavendar: Israeli AI, Surveillance, and Subject Formation

I am at work on a second book-length project, tentatively titled “The Scent of Lavendar: Israeli AI, Surveillance, and Subject Formation.” Here, I take the insights of subject formation in analog sites— prisons and torture facilities—to the digital realm. A central tenant of counter-revolutionary theories is the desire to know everything: to collect as much information as possible on the controlled population. Contemporary AI and surveillance technologies in Israel-Palestine complicate this story. Israeli means of surveillance not only collect information but affect subjectivities. In this project, I study the multi-layered contexts of surveillance and resistance in Israel-Palestine, to get at a broader story of how subjects are made and dominated. The contexts this project unpacks include the use of AI machines such as Lavendar in Gaza, facial recognition technologies towards Palestinians in Hebron, surveillance of Closed-Circuit TV in East Jerusalem, the evolution of the use of drones from the 1982 Israeli invasion of Lebanon to present day deployments by the military, settlers, and NGOs, Social media monitoring, and phone hacking. Combined, these technologies of the self tell a story about how control works through subjectivity.

Abolishing productive torture

Abstract

From 1948 until 2023, Israeli torture practices have become more sophisticated: they are no longer only openly violent but, while not completely departing from violence, have shifted towards the use of the tortured persons’ actions and relations. Testimonies collected by the Israeli NGO the Public Committee against Torture in Israel gesture towards this shift in the axis of sophistication and a correlated shift in another axis, that of subject formation. Twenty-first century Israeli torture affects subjectivity by attempting to stir the tortured person away from politics, build a fractured society, and sow suspicion and mistrust. Thus, alongside its repressive traits, torture is also aimed at the production of subjectivity through action and interaction. In so doing, Israeli torture expands analyses of torture that view its contemporary characteristics as “lite,” “psychological,” “no-touch,” or “stealthy” to include a view of torture as a political technology of domination qua subject formation.

Orchestrated life: subjectification in 1948 Israeli POW camps (forthcoming with Theory & Event)

Abstract

Between 1948 and 1950, the newfound State of Israel held around eight-thousand Palestinians captive in Prisoner of War camps. In contrast to objectification literatures that view POW camps as mere hangers for storing humans or understand prisons mostly as sites of death and attrition, these camps demonstrate otherwise. The POW camps were also sites for attempts at subject formation. Israeli officials, archival evidence reveals, asked to constitute the POWs as loyal workers who have internalized their defeat and have accepted Israel as an established fact. With these attempts, even if unsuccessful, the POW camps point political theorists towards the productive aspects of relations of power and demonstrate the work of subjectification as a process of binding to a certain truth.

Foucault’s anti-limitative critical practice

Abstract

Recent advancements in the study of Foucauldian genealogy view it as “problematization” and as “possibilizing:” opening a path towards change. Analyzing genealogy from Foucault’s practical endeavors paints a more elaborate picture. Foucault’s writings on the prisons information group, the Iranian uprising, and gay liberation elucidate the transgressive transfigurative aspects of genealogy. What I call the anti-limitative critical practice of “transgressive transfiguration” is the positive creation of a different reality based on the genealogical investigation of the current reality. These endeavors show that genealogy is not only a site of problematization or one that is possibilizing. It also creates a change in reality. What Foucault calls a “transfiguring play of freedom” is based on challenging limits placed on people that are presented as universal. This anti-limitative critical practice expands our understanding of genealogy and at the same time provides the normative compass Foucault was so often accused of lacking.

Foucault and the Prisons’ Information Group’s Counter-subjectivation

Abstract:

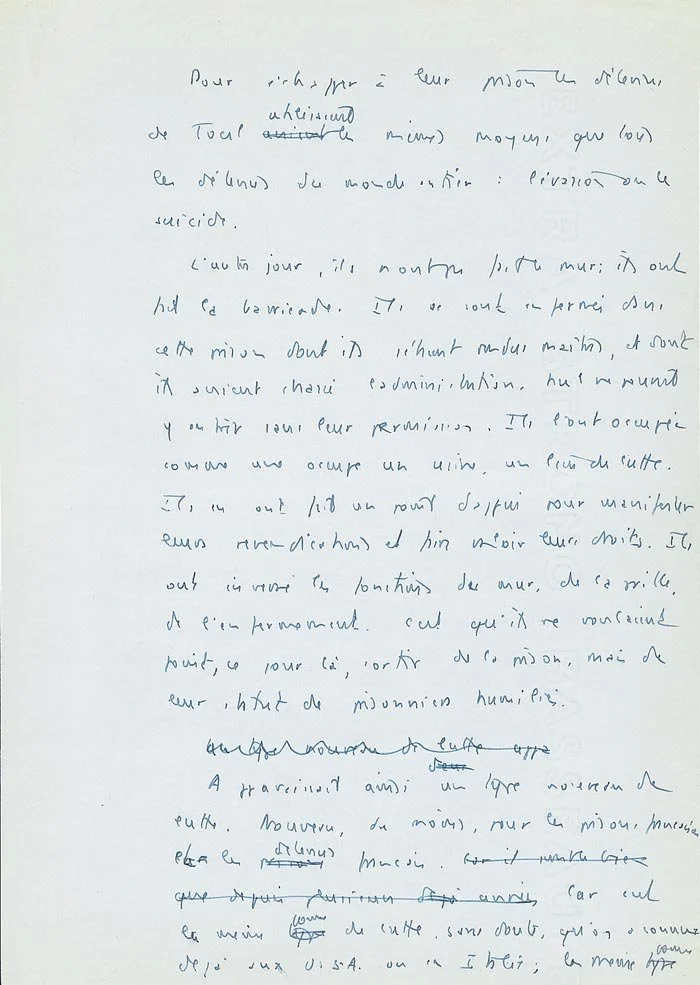

Between February 1971 and December 1972, Michel Foucault took part in the Prisons Information Group (Groupe d’Information sur les Prisons, hereafter GIP). With demonstrations, publications, and direct-action, the GIP sought to intervene in France’s carceral array as a set of systems, ideas, and practices. Foucault and the GIP’s goal was not simply to improve imprisonment conditions but to intervene in the constitutive conditions of the prison. The archives left by Foucault’s involvement with the GIP alongside Foucault’s lectures and publications enable political theorists to better understand our carceral moment and the search for a path beyond it. Reading Foucault’s tracing of the genealogy of the category “guilty” and the GIP’s analyses of prison uprisings allows an understanding of what I refer to as “democratic counter-subjectivation.” In opposition to the structures of carceral subjectivity where incarcerated people could never influence the standards according to which prisons ask to “rehabilitate” them, Foucault and the GIP call our attention to a more democratic work of subject formation. Instead of transcendentals left outside incarcerated people’s reach, they propose the possibility of political and collective self-transformation. Reminding us that the prison itself was a product of abolition, that of the previous cruel mechanisms of punishment, they offer timely direction to the work of abolition. Instead of the search to balance the horrors of mass-incarceration and racial inequality with a more proportionate or equal prison, the GIP linked carceral structures of unfreedom with political realities outside prison walls and proposed an intolerance to these carceral politics.